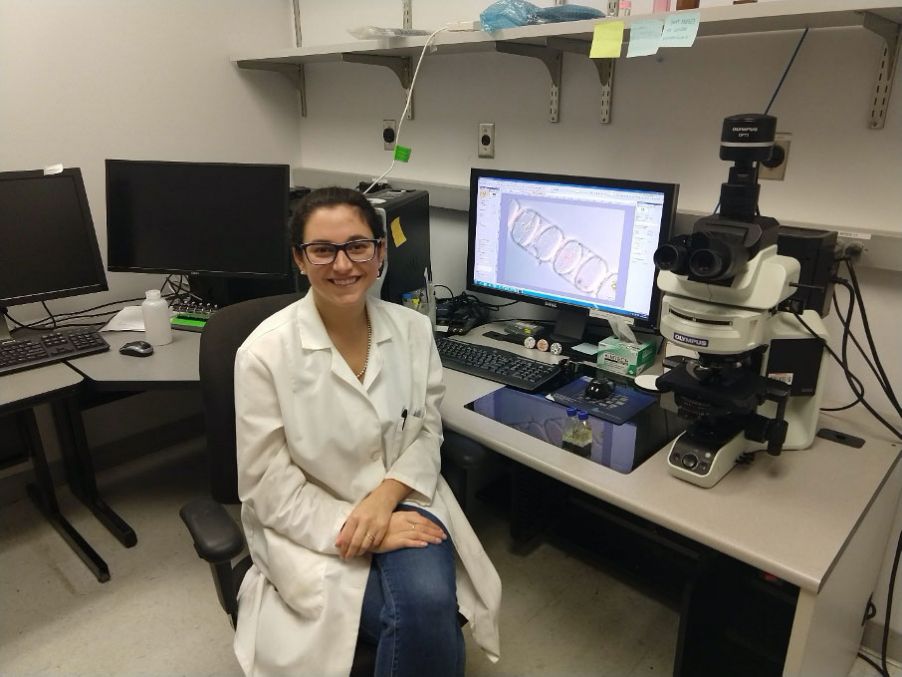

In the Schnetzer lab at North Carolina State University

Gabrielle Corradino, Ph.D. is a Biological Oceanographer breaking new ground in our understanding of one of the most important—and understudied—organisms on the planet: plankton. Specifically, Dr. Corradino studies a little-known plankton called nanoflagellates to better understand their role in the food web. In addition to her research, Dr. Corradino also works in marine policy. She’s a committed educator who feels strongly about science communication and teaching the next generation. I interviewed Dr. Corradino to learn about her journey as a scientist, the role microscopes play in her work, and the importance of communicating with the public.

Joanna: Who helped inspire you to become a scientist?

Gabrielle: When I was younger, I didn’t formally know much about marine science, but I knew I loved the ocean. In 5th grade, I met Sylvia Earle, a well-known marine scientist who has been involved with everything from research to policy to education. She shaped a lot of how I see science. She taught me that scientists cannot be isolated, and we have to involve others.

Joanna: Do you remember the first time you used a microscope?

Gabrielle: Yes! I was in 6th grade, and it was my first time in a science lab. We were looking at pond water under the microscope and I remember looking at paramecium and at a butterfly wing. It was mesmerizing. I ended up getting nauseous because I kept zooming in and out while examining each slide. I was so amazed that I asked my dad to get me a travel microscope the following Christmas.

When I finished my undergraduate education, I started working in an ecology lab looking at many of those same pond organisms. Sitting at the lab bench brought me back to 6th grade.

Joanna: Your experiences as a child clearly shaped your passion. What should we be doing to get more young people involved in the sciences?

Gabrielle: That’s a really important and very big question. I think about this a lot—how do I make my research more meaningful to students to help inspire the next generation? I think that it’s important to empower students as much as possible. Empower them to be explorers and be their own scientists. Ask questions, go out into the field, and try to find the answers. Connect with your curiosity.

Once someone connects with their natural curiosity of wanting to know more, science becomes a much more authentic experience. It's not just a homework assignment, it's not just something they’re doing for school. It's something they’re doing for themselves. I think that when we speak to younger students about science, we need to do more showing instead of just lecturing. Show them how they can answer their own questions, don’t just give them the answer. Even if it’s just an internet search or a simple experiment, the most important part is that they are finding the answers for themselves. Show the younger generation that they have that ability. I think that’s the way forward.

Gabrielle with her PhD advisor Dr. Schnetzer (image courtesy North Carolina State University).

Joanna: How were you empowered to go from liking marine biology to researching plankton?

Gabrielle: I’ve always been question oriented, especially around organism behavior. It has taken different forms, but I landed on plankton for my PhD because my advisor’s passion for plankton really got me hooked. Plankton are an understudied area of marine science, and there are still many unidentified species. In fact, plankton are not a single species; the term actually refers to any organism that cannot swim against the current and can range from the smallest bacteria to sunfish. The focus of my research is a tiny plankton called nanoflagellates.

Two types of plankton: the larva of a barnacle (Zooplankton nauplius) (left) and the head of a water flea (right). Images courtesy Gabrielle Corradino.

Joanna: Nanoflagellates are so small—how do you image them?

Gabrielle: Typically, I use DIC (differential interference contrast) at 60x magnification. I can do 40x, but you really need 60x–100x for measurements. The nanoflagellates are fast and move quite a bit, but if I get them under the right conditions or when they’re attached to a particle, they are pretty easy to image with DIC. To watch them feed on smaller plankton, I would also observe them under fluorescence to see if they ingested fluorescent beads. For my PhD work, I used a BX53 microscope with an Olympus camera.

Diatoms (phytoplankton) from North Carolina. Image courtesy Gabrielle Corradino.

Joanna: Is there one image you’ve captured that you’re particularly proud of?

Gabrielle: There’s one—it’s not a “great image” but it was a breakthrough for me. I set up an experiment to see if it had ingested a fluorescent bead. When I was able to image the plankton having ingested the bead, I was excited because I knew my experiment could continue. The hard work had paid off.

Joanna: I know communicating your research to the public is an important part of what you do. How have changing public perceptions about science impacted your work?

Gabrielle: While public perception can change depending on what they’re seeing or reading about science, the scientists just keep going. The science keeps getting done. It’s our job to initiate better communication with the public and tell our story.

I was never formally taught how to break down that barrier between science and the public in college, and it’s something I’ve worked hard at learning since. I think there has to be buy-in from universities to effectively teach science communication at multiple levels from students to full professors. With my current work in marine policy, I’ve worked on my communication skills because I need to be able to communicate the important educational work that is going on within the NOAA.

I remember during my written exams in graduate school, my committee member asked: “You’re in an elevator with the President, and you have 5 minutes to explain your research. What do you say?” It was and is a tough question and is good practice as a scientist to always think about how to reach a broader audience through clear communication. It is an important point to spend time thinking on.

Joanna: So, if you won the grant lottery, where would your curiosity take you? What would be your dream research project?

Gabrielle: I’m going to cheat and do a part A and B. First, I’d set up a long-term ecological research station as a professor at a local university and teach undergraduates how to regularly monitor plankton and check for toxins. I’d love to monitor for plankton and also have the station be affiliated with a high school. I’d like to have students test their local waters so that they become stakeholders of their waterways and this monitoring program. I think high school is the sweet spot for starting to train the next generation. I would have the ability to reach them before college where they can major in the sciences and not just take science electives.

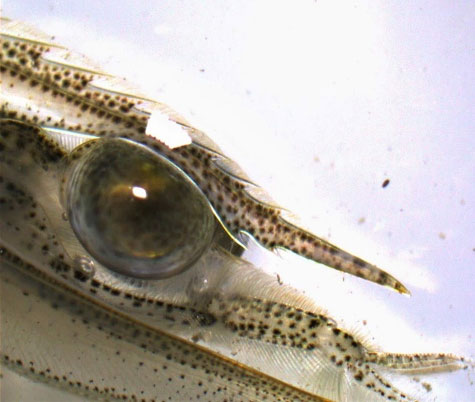

Close-up of a shrimp captured at the Center for Marine Sciences and Technology (CMAST) in North Carolina. Image courtesy Gabrielle Corradino.

Dr. Corradino recently took over our Instagram page! Make sure to follow her @MarchofthePlankton on Instagram to see the takeover and learn how Gabrielle is studying the world around her.

.jpg?rev=FDF1)